EXHIBITION

At its top /

ABOUT

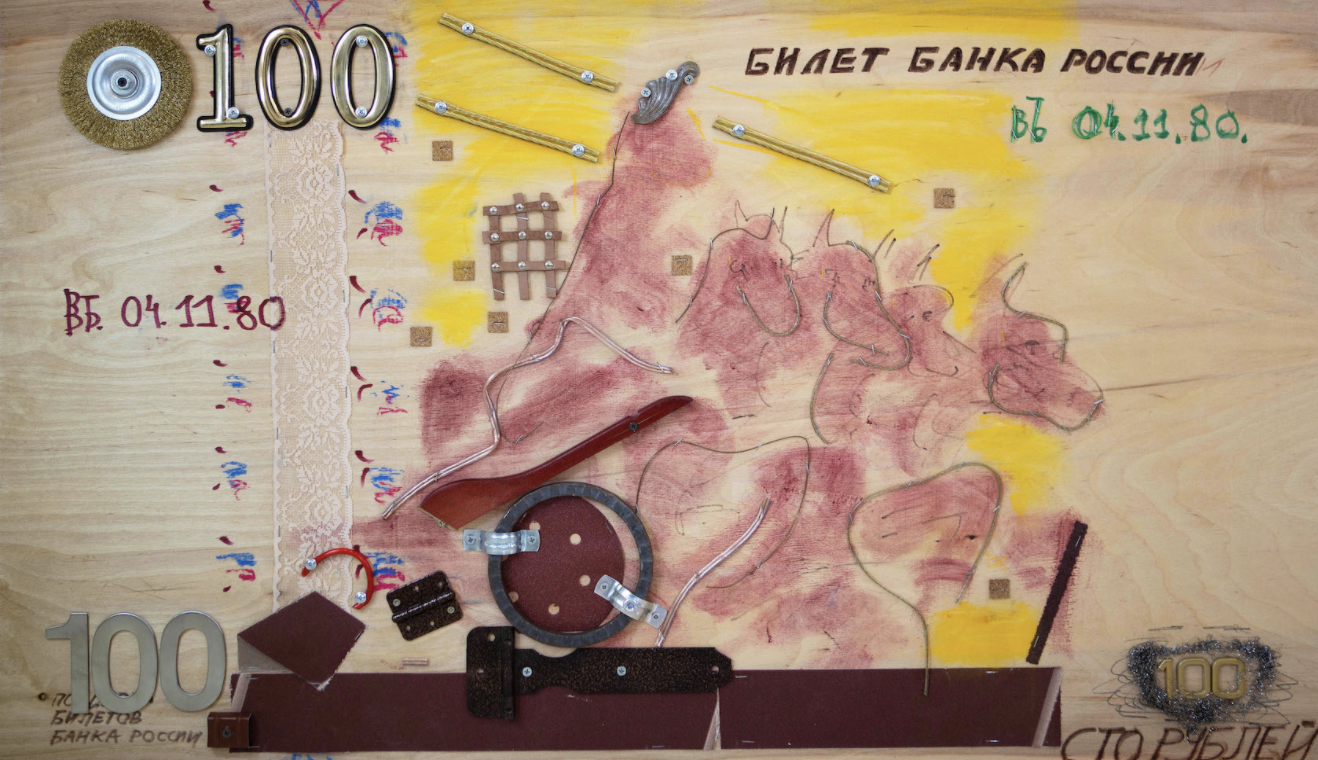

Petr Bystrov (b.1980, Moscow) is a co-founder and member of the Radek society. He uses a technique he invented—skobogravyurа ("staple etching")—to make assemblages from wood, metal elements, and scrap. He makes use of construction staples, paper clips, wire, parts of mechanisms, and appliances to make fancy portraits, mythological scenes and banknotes on plywood. The artist created 10 wooden assemblages of banknotes for his show: 100 USD, 100 Euro, 100 Yuan… ⠀

In The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, Warhol wrote, 'I like money on the wall. Say you were going to buy a $200,000 painting. I think you should take that money, tie it up, and hang it on the wall. Then when someone visited you the first thing they would see is the money on the wall.' Ostap Bender, the protagonist of Ilf and Petrov's novels The Twelve Chairs and The Golden Calf, 'loved and suffered' – 'loved money and suffered from a lack thereof'. Warhol and Bender referred to paper money, banknotes, a fading substance in the time of a global pandemic. The Bank of Russia predicts that the share of non-cash payments in retail will reach 70% by the end of 2020. And this is a great chance to take a fresh look at this nostalgic medium of exchange.

In The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, Warhol wrote, 'I like money on the wall. Say you were going to buy a $200,000 painting. I think you should take that money, tie it up, and hang it on the wall. Then when someone visited you the first thing they would see is the money on the wall.' Ostap Bender, the protagonist of Ilf and Petrov's novels The Twelve Chairs and The Golden Calf, 'loved and suffered' – 'loved money and suffered from a lack thereof'. Warhol and Bender referred to paper money, banknotes, a fading substance in the time of a global pandemic. The Bank of Russia predicts that the share of non-cash payments in retail will reach 70% by the end of 2020. And this is a great chance to take a fresh look at this nostalgic medium of exchange.

read more

This is not the first time Petr Bystrov, an adherent of his own philosophy of 'excess and lack, unwieldy triviality' (a quote from a conversation with A. Evstratov, 2008), has addressed the subject of money. Bystrov creates art objects from materials purchased from construction supplies shops, using a signature technique that he named staple-engraving. When depicting banknotes with 100 denominations (rubles, yuan, dollars, euros, etc.), he uses a wide range of media, abandoning the rigidity of readymades in favour of graphic and pictorial expression, which is why strokes of bright paint and handwritten inscriptions pop up here and there across the wooden money.

Indeed, a banknote cannot be rendered exclusively in staples, wires, shreds of fabric, that is, materials of the same origin. It has many layers. The image itself is only an external, superficial level of political symbols designed to tell the world about the pride of a particular nation. Only watermarks, embossing, textured inserts can breathe life into a piece of paper with a numerical symbol. Using a range of materials, Bystrov conveys the most precious feeling banknotes provide – the feeling that they belong to you.

The public and visual aspect of the One Hundred Percent show possesses a side hidden from a superficial glance, which is a new series of portraits. Bystrov often creates images of his cultural idols. His gallery includes the portraits of Daniil Kharms, John Lennon, Semyon Budyonny, Mikhail Lermontov, Karl Lagerfeld. This time the artist has made engravings based on his family members and friends. Being exhibited next to banknotes does not devalue these images – on the contrary, it illustrates a simple dialectic of the essentials. We need close people, we need money, neither makes much sense without the other.

A former member of Radek Society and School of Contemporary Art – radical youth art projects of the 90s, – Bystrov has long been examining the relationship between labour and value, gesture and meaning. In 2006, at Radek Society's LIE show at the Marat Guelman Gallery, Bystrov and his associates publicly exposed, as an exhibit, the budget of the entire show. How much does a work on paper affect the viewer, and how much does it translate into in monetary terms? What about objects made of wood, tin, crayons, and acrylic?

Money has long been divorced from labour. The randomness of its correlation with the expended effort makes money a close relative to art. It too can look simple, yet rich, like sudden luck of a gambler. Bystrov's spiritual mentors, the artists featured in the early Jack of Diamonds exhibitions in Moscow, knew this. They painted playing card faces and self-portraits depicting them as strongmen and pugilists, not disdaining the commercial intelligibility and terseness of the sign. A sign is an architectural element of a building, a part of its facade. The materials of Bystrov's staple engravings are ultimately architectural too – their solidity alludes to everyday inhabited spaces, whose value, again due to the pandemic, has increased many times over.

Valentin Diakonov

Indeed, a banknote cannot be rendered exclusively in staples, wires, shreds of fabric, that is, materials of the same origin. It has many layers. The image itself is only an external, superficial level of political symbols designed to tell the world about the pride of a particular nation. Only watermarks, embossing, textured inserts can breathe life into a piece of paper with a numerical symbol. Using a range of materials, Bystrov conveys the most precious feeling banknotes provide – the feeling that they belong to you.

The public and visual aspect of the One Hundred Percent show possesses a side hidden from a superficial glance, which is a new series of portraits. Bystrov often creates images of his cultural idols. His gallery includes the portraits of Daniil Kharms, John Lennon, Semyon Budyonny, Mikhail Lermontov, Karl Lagerfeld. This time the artist has made engravings based on his family members and friends. Being exhibited next to banknotes does not devalue these images – on the contrary, it illustrates a simple dialectic of the essentials. We need close people, we need money, neither makes much sense without the other.

A former member of Radek Society and School of Contemporary Art – radical youth art projects of the 90s, – Bystrov has long been examining the relationship between labour and value, gesture and meaning. In 2006, at Radek Society's LIE show at the Marat Guelman Gallery, Bystrov and his associates publicly exposed, as an exhibit, the budget of the entire show. How much does a work on paper affect the viewer, and how much does it translate into in monetary terms? What about objects made of wood, tin, crayons, and acrylic?

Money has long been divorced from labour. The randomness of its correlation with the expended effort makes money a close relative to art. It too can look simple, yet rich, like sudden luck of a gambler. Bystrov's spiritual mentors, the artists featured in the early Jack of Diamonds exhibitions in Moscow, knew this. They painted playing card faces and self-portraits depicting them as strongmen and pugilists, not disdaining the commercial intelligibility and terseness of the sign. A sign is an architectural element of a building, a part of its facade. The materials of Bystrov's staple engravings are ultimately architectural too – their solidity alludes to everyday inhabited spaces, whose value, again due to the pandemic, has increased many times over.

Valentin Diakonov

EXHIBITION

VIEWS

VIEWS

ARTIST

Artist and curator Peter Bystrov was co-founder and Radek Community (1997-2008, community was founded in Moscow by a young group of the leftist artists, musicians and art critics).

In 2005 - 2007 Bystrov worked as a visiting professor at New Academy of Fine Arts (NABA), Milan.

Currently creates assemblages – «bracket engravings» on wood from metal and garbage elements. Constructing socio-historical and national types, raises questions of self-identification of the modern inhabitant of a big city. Nominee of the Kandinsky Prize (2007) and the «Innovation» (2008). Lives and works in Moscow.

In 2005 - 2007 Bystrov worked as a visiting professor at New Academy of Fine Arts (NABA), Milan.

Currently creates assemblages – «bracket engravings» on wood from metal and garbage elements. Constructing socio-historical and national types, raises questions of self-identification of the modern inhabitant of a big city. Nominee of the Kandinsky Prize (2007) and the «Innovation» (2008). Lives and works in Moscow.